Linguistic Origins of the Naming of San Francisco’s Islais Creek

- Evelyn Rose

- Jul 13, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2025

(This article is an updated version of one originally published in the Spring 2020 issue of the Glen Park News, a publication of the Glen Park Association of San Francisco.)

Is it pronounced Is-liss? Maybe it’s Is-lay-iss? Or Is-lay? What about Iss-lye?

Given that no one seems to know how to say it, it may not be surprising that both the pronunciation and phonetic origin of the name of Islais Creek, the largest creek in San Francisco, has long been a matter of debate.

The course of Islais Creek

Islais Creek has two main tributaries. Both emerge from aquifers beneath the tortuous Peninsular Divide that extends from Golden Gate Strait southward to beyond the San Mateo County line. One tributary flows from the base of San Bruno Mountain in the Crocker-Amazon, a district on the southern edge of San Francisco. The other flows from the southern slopes of Twin Peaks at Portola Boulevard, near the city’s geographic center. It then snakes its way southward through the 70-acre Glen Canyon Park Recreation Area before turning to the southeast. It converges with the first tributary near today’s Lyell Street and Alemany Boulevard.

Islais Creek then flows to the east into the what was once a 2-mile-wide inlet at San Francisco Bay near today’s Cesar Chavez and Third Streets. Fanning out from the modern Interstate 280 and U.S. Highway 101 interchange, what had once been a thriving natural landscape is now covered in asphalt and concrete. The Islais Creek wetlands were not only home to an abundance of fowl, fish, and wildlife but also at least three permanent villages of the Yelamu tribe of the Ramaytush Ohlone.

The flow of Islais Creek was so abundant that, following its charter in September 1860, the Spring Valley Water Company diverted an estimated 400,000 gallons daily as a temporary water supply for thirsty San Franciscans. The service was discontinued in July 1862 following the completion of a redwood flume and installation of iron pipes that extended from Pillarcitos Creek in San Mateo County northward into the city.

Though it was diverted into San Francisco’s combined water and sewer system just over a century ago, Islais Creek still follows its historic course underground. Today, only two of San Francisco’s creeks continue to be daylighted: Lobos Creek in the Presidio, and a portion of Islais Creek north of the Glen Canyon Park Recreation Center, the latter creek being a shadow of its former self.

What’s in a name?

After more than 200 years of conjecture and possible misinterpretation of fact, it is no surprise that we continue to struggle with the pronunciation of Islais. Let’s look at the proposed origins of the name and, as we do, add a new possibility to the queue.

First, what Islais Creek is not. The United States Coast Survey map of 1857 identifies the creek as Du Vree’s Creek. The origin of this name has been a mystery, but research has revealed new insights.

The first mention of a William Dufrees appears in the Daily Alta California in September 1851. In a description of the ticket for that year’s upcoming election, Dufrees is running for San Francisco County justice of the peace. In an article a few months later describing the proposed route of the Pacific & Atlantic Railroad, as it crossed the city’s Precita Creek, "…the line then crosses Islar's Creek and is conducted along the slope of the high ground at the head of the marsh three fourths of a mile above Capt. DeFrees' house." Then, in a March 1852 article in the same paper, “Captain DeVries, a gentleman who resides four miles south of Mission Dolores and who has between thirty or forty acres of land under cultivation,” was highlighted for the wagonloads of fresh vegetables he was transporting into the city daily.

According to contemporary maps, the distance from Mission Dolores to the railroad crossing at the so-called Islar’s Creek is only about two miles. However, going four miles to the south of Mission Dolores would generally place DeVries in today’s Crocker-Amazon district, near the source of the creek’s San Bruno Mountain tributary. In either case, it seems the captain was indeed situated somewhere along the creek. Yet, because his first name is never shared in these reports, and that there seem to be so many phonetic options for spelling the name De Vries, we may never know his true origins. But one additional piece of information may provide a clue.

In December 1849, a German-born sailor by the name of Adolphus Windeler arrived in San Francisco aboard the American sloop Probus. They had set sail from New York 178 days earlier with 32 passengers and a cargo of prefabricated iron houses, stoves, furnaces, tin ware, and lumber. With the Gold Rush in full swing, the crew soon abandoned ship and headed for the Sierra foothills. Windeler notes in his diary that the commander of the Probus was a Capt. DeVries, which is confirmed by other maritime records. While moored in Yerba Buena Cove among a forest of ships’ masts, the captain may also have been consumed by the excitement and decided to abandon ship himself.

Native Californian or Spanish derivation?

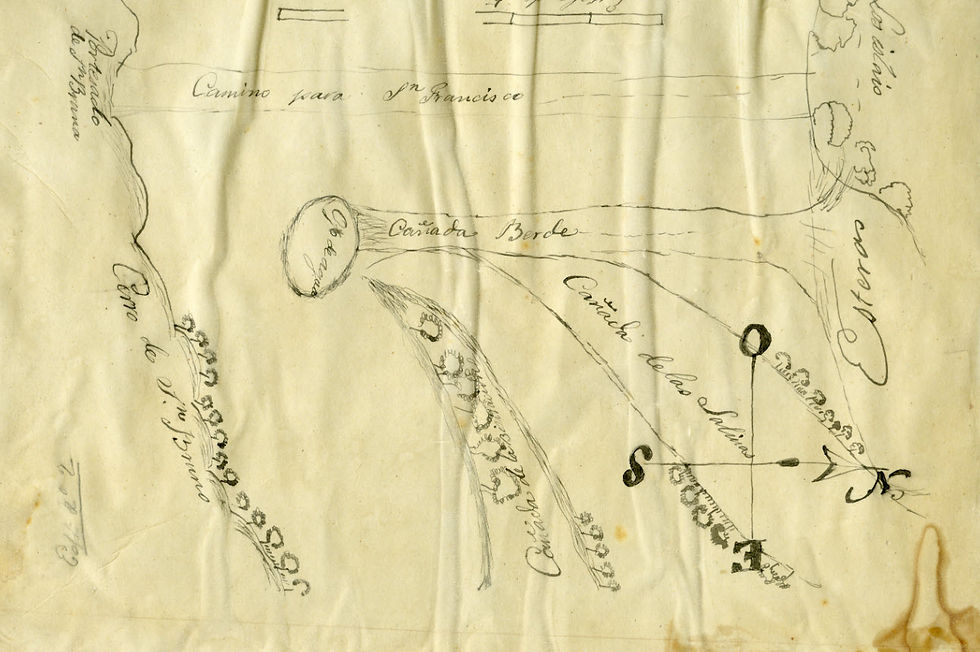

One of the earliest appearances of “Islais” or “Yslais” on Spanish maps occurs in the mid-1800s. A hand drawn map from the Spanish and Mexican Land Grant Records of the Salinas y Visitacion Rancho of San Francisco, dated 1834 and housed at the California State Archives, includes the words, Los Islais.

The earliest use on American maps is the Clement Humphreys Map of San Francisco published in 1853. Then in 1857, José de Jesús Noé submitted court documents in San Francisco for obtaining an American patent for his 4,443-acre Rancho San Miguel that had been granted to him by Mexican governor Pío Pico. It included a map that identified an Arroyo de los Yslais next to a peñasco just south of Precita Creek (see maps below).

In Spanish, peñasco refers to a “large crag or rock.” In fact, a large rock with an elevation of over 40 feet was represented on several San Francisco topographic maps into the 1870s, as well being visible in a 1912 photograph of the region. Because of urban development and freeway construction, the rock no longer exists. However, it would have been located on the east side of today’s Glen Park Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station near Bosworth and Lyell Streets and adjacent to the course of the Twin Peaks tributary of Islais Creek.

The word Islais has no direct meaning in Spanish. Pedro Fages, a Spanish soldier who traveled with the Portolá expedition in 1769 and later became governor of Alta California, would be the first to transcribe the term “yslay.” It is believed that he first heard the term while among the Salinans of Salinas Valley in today’s Monterey County. According to later researchers, Fages’ definition is very clear that the term referred to the holly-leafed cherry (Prunus ilicifolia) that grew abundantly along the banks of creeks and was a highly valued food among the native peoples of the California coast. It is theorized that since the explorers/conquerors had no Spanish name for the plant, they had adopted the native moniker. By the early 1800s, it had become part of the California Spanish lexicon.

Anthropologists, linguists, and naturalists have generally agreed that Islais is a modern spelling of the Native Californian name for the holly-leafed cherry. In the 1940s, Smithsonian ethnologist John P. Harrington declared the word ‘slay’ to be of Salinan origin. As noted earlier, the Salinans lived in today’s Salinas Valley, and their language is recognized as being similar to that of the Chumash of the Santa Barbara region farther to the south. Yet, the Costanoan language of the Ohlone, whose territory ranged from Santa Cruz north to Golden Gate Strait, is unrelated to the Salinan language. And to further complicate matters, Harrington has been accused of developing "his translations of native terms into a mixture of English, Spanish, and sometimes other languages," to the dismay of future researchers tasked with interpreting his work.*

In 1945, Thomas P. Brown, recognized by some as an expert of California place names, also declared that the name "Islay" was from the Native Californians farther south. Yet that same year, Erwin G. Gudde, in an article in California Folklore Quarterly, remarked that Brown's conclusion, "smacked of popular etymology."† But then without evidence, Mr. Gudde goes on to proclaim that he is going with the spelling of Islar that he had found in a report of a railroad engineer published in 1851 (the Pacific & Atlantic Railroad report described above). He notes that while, "other names in the report are spelled fairly correctly we may assume that Islar was the original and proper form."† So much for evidentiary research! Mr. Gudde seems to have been an expert of popular etymology himself.

Moreover, it does not appear that the holly-leafed cherry was at all abundant in San Francisco. In fact, there is no evidence in either historical or scientific literature that documents the existence of native Prunus icifolia north of San Mateo Creek and San Bruno Mountain. This, then, may open the door to another possible origination of Islais.

In 1935, one Henry W. Turk advanced a new theory in the "Knave" section of the Oakland Tribune. He shared that according to “old residents” he had spoken to, Islais Creek had been named for a Frenchman named Florencio Islais who raised frogs and watercress along the creek, and who had died some years before. Other than Florencio’s proposed national origin and occupation, Mr. Turk may not have been too far off the mark.

In March 1907, an obituary appeared in the San Francisco Call entitled: “SCION OF OLD MEXICO CITY DIES IN CITY. Islais Creek is Said to Have Received Name From His Ancestors.” As told in the article, Florencio Yslas (1838-1907), a member of a “prominent family of early California,” had claimed to be the grandson of the man for whom the creek was named. The difference in spelling between Yslas and Islais was said to be due to the differences between English and Spanish pronunciation and spelling.

Before his death, Florencio and his daughter had shared that he had traveled overland to California from Sonora, Mexico in 1849 with his father, José Francisco Yslas. According to Catholic Church records in Sonora, Mexico (available at Ancestry.com), a male infant named Florencio was born on October 10, 1838, to Francisco Yslas (1801-1885) and Maria Bernal (1815-1887). Sonoran church records also confirm that Francisco Yslas was the son of Teodoro Yslas (1772-1833) and Ana Maria Anza (1775-1859), and that Ana Maria was the daughter of Captain Juan Bautista Anza II (1736-1788), leader of the 1776 expedition to San Francisco that established the sites for the Presidio and Mission Dolores. Therefore, Florencio’s grandfather was Teodoro Yslas, for whom the creek was claimed to be named. But who named the creek, when was it named, and why was it named for Teodoro? Could the creek have been named by Juan Bautista Anza?

Prior Spanish expeditions had arrived and departed the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula along a route that hugged the Pacific coast. While Anza also arrived via the ocean route, he would be the first European to depart through the middle of the Peninsula before turning southwesterly toward the ocean, possibly along an extant trail established by the Ohlone centuries before. This same route would soon become known as the original El Camino Real, and in the American Period as the Old San José Road. The road passed through today’s Fairmount Heights and Glen Park before turning south near the modern intersection of Diamond and Chenery Streets. It is this general area where Anza would have first encountered the future-named Islais Creek.

At the time of the Anza expedition in 1776, Teodoro would have been about 3-1/2 years old. Would Anza have known Teodoro at this time? Both were living in the state of Sonora in 1776 but there appear to have been at least 150 miles between their places of residence. Furthermore, Anza died in 1788, 10 years before his daughter, Ana Maria, married Teodoro. So, it is possible the two men never met.

Then perhaps the name of Islais Creek was bestowed in Teodoro’s memory. The earliest known appearance of Islais on maps is 1834 (the Salinas y Visitacion Rancho map described above), one year after Teodoro’s death. If these map makers did, in fact, bestow the name of Los Islais in his memory, then why not use Los Yslas? Unfortunately, the details of by whom, when, and why have been erased by the passage of time.

So in the end, which theory might be more correct? Is Islais Creek named for the holly-leaf cherry, islay, or for Juan Bautista Anza’s son-in-law, Teodoro Yslas? Fages may have indeed documented a word for the cherry that was used by the Salinans and Chumash. However, without native holly-leafed cherries growing along creek banks in San Francisco, it seems unlikely that the term would have been in common use among the Yelamu, whose language was unrelated to the tribes to the south. This, therefore, may give more credence to Florencio Yslas’ claim that the creek was named for his grandfather, Teodoro, but gaps in the historical record exist. With the comingling of languages while defining Native California terms, mixed with intermittent episodes of popular etymology, the origin of the name of Islais Creek will forever remain a mystery.

Language differences, varying interpretations by researchers over time, and forgotten recollections of long-passed residents have forever muddled Islais Creek’s true namesake. And about that pronunciation? According to online Spanish-to-English translation resources, “Yslas” is pronounced “EES-liss.”

*See Anderton A. J. The Spanish of John P. Harrington's Kitanemuk Notes. Applied Psycholinguistics, Vol. 15, No. 1 (December 1994), pp. 437-447.

†See Gudde E. G. Places and Names. PAGING MESSRS. DARDENELLES AND ISLAR. California Folklore Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 3 (July, 1945), pp. 281-284.

Comments