The World Came to Him: On the Bridge Beat with CHP Officer Jack Symons

- Jan 26, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Jan 27, 2024

THIS POST DISCUSSES A HISTORY OF SUICIDES ON THE GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE.

IF YOU ARE CURRENTLY EXPERIENCING A CRISIS, PLEASE CALL THE 988 SUICIDE AND CRISIS LIFELINE.

DIAL 988 OR VISIT 988LIFELINE.ORG FOR MORE INFORMATION.

The opening of the Golden Gate Bridge on May 27, 1937, was a tremendous affair. "Queen Crowned as Throngs Open Span," hailed the San Francisco Examiner. "Visitors From All Over Continent at Coronation Ball. There's a new bridge ready and a city roars with pride. The builders have departed; the celebrators are here. The Golden Gate is vanquished, a broad highway hung above its mile wide chasm; San Francisco and her close drawn neighbors are delirious with joy."

At that time, the iconic structure truly was the “Queen of them all.” It was the longest and tallest suspension bridge in the world, titles it would hold for decades. Since then, it has become one of the most recognizable, photographed, and visited landmarks in the world.

So, when Glen Park resident and California Highway Patrol officer Jack Alvan Symons learned in late 1953 that he would be patrolling the great Bridge serving as the gateway to the Redwood Empire, he must have been excited and proud. Yet in that moment, Symons may not have foreseen how the oath he had taken, in part to, “Assist those in peril or distress, and, if necessary, lay down my life rather than swerve from the path of duty,” would soon be tested many times over.

Early Days

Born in 1916 in San Francisco’s Holly Park neighborhood, Symons was the youngest child of Alvan W. Symons of Thornbury in Devon, England, and California-born Idell May Russell. As a member of the Balboa High School Class of 1933, he and other graduates were asked to share a parting quote that appeared in the yearbook next to their senior picture. Symons proclaimed, "Let the world come to me."

Senior picture of Jack Alvan Symons in The Galleon, Balboa High School, San Francisco, California, 1933. Image courtesy of Ancestry.com.

After graduation, Symons began work as a patternmaker at Bethlehem Steel in San Francisco. When he married Evelyne Battles in 1937, the couple moved in next door to her parents’ home on Bosworth Street near Diamond. But upon his return from World War II Navy service, Jack and Evelyne parted ways. By 1950, Jack was married to Marilyn Nadine Steinberger, a registered nurse from Forest City, Iowa. They and three children moved into a quaint home just a few blocks west of Symons’ first residence on Bosworth, near the intersection with Elk and Congo.

On the Bridge Beat

Symons began his law enforcement career in 1948 with the San Francisco Police Department and by 1953, he had joined the California Highway Patrol. After a stint in Bakersfield, he transferred back to the Bay Area and started his beat on the Golden Gate Bridge.

On November 30, 1953, while driving his patrol car southbound on the Bridge, Symons saw a young woman, 24-year-old Marie L. McCormick of San Francisco, climb over the rail on the Bay side about 200 feet south of the North Tower. According to reports, Symons "…jerked his car around in a U-turn and, as he leaped from it, spotted the girl clinging to the girder below the rail. 'Wait a minute!' he cried, racing toward her. At that moment she jumped. He watched helplessly as her body disappeared in the waters far below." After Marie's body was recovered, rescuers found a note in her pocket that explained she had been distraught over her parents’ pending divorce.

Less than two weeks later on December 11, Officer Symons was notified by Bridge authorities that a car had been abandoned on the span. After arriving on the scene, Symons saw a man standing on the outside of the railing looking down at the water. "Wait a minute!" Symons yelled as he walked over. He later described how the man, "...just looked at me and stepped off." The wife of San Mateo realtor Arthur R. Burt, 61, later shared that her husband had been recovering from a "nervous breakdown" and had recently been showing signs of a relapse.

And one week after that, on December 18, 1953, Gustave F. Aguilar, 58, described as a pioneer automobile dealer from Richmond, left his Cadillac running in a northbound lane at mid-span and jumped. Symons arrived just a few minutes after. Witnesses explained how Aguilar had stopped his car and, "Then he vaulted over the rail. It happened just like that." Aguilar left no note, and his family had no explanation. Friends described him as having been happy and joking during a birthday party the previous evening.

Sadly, Marie, Arthur, and Gustave were not the first to end their lives on the Golden Gate Bridge. Only three months after its grand opening in 1937, the first person to die by bridge suicide from either the Golden Gate or the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge was Harold B. Wobber of Oakland. A World War I veteran, he had been suffering for nearly 20 years from “shell shock,” a condition known today as post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

The Safety Net

Had a suicide deterrent been in place, perhaps some or all these souls might have reconsidered their fateful decision. Ironically, while there was no safety net for the public, there was one for workers and its value as a life-saving measure had already been proven many times over.

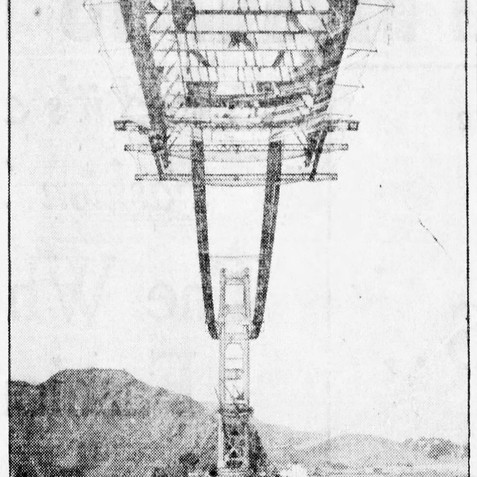

By the time the Golden Gate Bridge was 70% complete, not a single worker had yet lost their life (compared with a total of 24 workers who had perished during construction of the Bay Bridge). To help maintain that remarkable record and given the incredible danger all workers faced, on May 4, 1936, Chief Engineer Joseph B. Strauss proposed what was described as an "elaborate" measure: a safety net.

Golden Gate Bridge directors quickly ordered Bethlehem Steel to begin constructing "four big traveling frames" that would be suspended from cranes and travel from tower to tower as work progressed. The net would be constructed of 2-square-inch mesh cotton twine, 110 feet wide, 4,200 feet long, and stretched across the channel 15 feet below the deck. It would be "swung out close under the areas of steel erection, strong enough to catch any workman who may fall."

Images of the "elaborate" safety net for Bridge workers. From the Santa Rosa Republican (Santa Rosa, California), September 4 and October 5, 1936. Courtesy of Newspapers.com.

By October 1936 and at a cost approaching $100,000 (about $2.2 million today), the net was fully installed. This was the first time in history that a safety net had been used at any construction site. The Fresno Bee acknowledged that, "If it saves one life it will be a good investment."

And on October 8, 1936, that investment was realized when Ward Chamberlain, an employee of Bethlehem Steel, became the first to prove its utility. After slipping while bolting a floor beam, Chamberlain fell 15 feet into the net. Shaken but alive, he walked away with only minor injuries.

In another incident, however, the net did not function as planned. In October 1936, 30-year-old steelworker Alfred Zampa fell into the net on the Marin side. Rather than staying taut, the net sagged down an extra 10 feet, crashing him into the ground. Zampa broke 4 vertebrae and was not expected to survive. But after 2 years of recovery, he was able to walk the girder of the Golden Gate Bridge one more time, just to prove he could do it.

Zampa spent the remainder of his life in Crockett, where in 1927 he had worked on construction of the first Carquinez Bridge. As the decades passed, he became a pillar of the community. Contrary to his medical prognosis, he lived a full life until 2000 when he passed away at the age of 95. Today, the second Carquinez Bridge on westbound Interstate 80 between Vallejo and Crockett is designated as the Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge, the only bridge named for a blue-collar worker in the United States.

About 2 weeks after Zampa’s fall and with construction nearly 90% complete, the Golden Gate Bridge suffered its first worker fatality. As a derrick collapsed on the Marin side, crushing the operator inside, it pushed a second worker off the Bridge into the safety net. That worker survived with injuries. Then in January 1937, a riveter on the Bridge fell into the net from the center span. He was saved, as well.

But just one month later, on February 17 and only 3 months shy of opening day, a 10-ton platform and scaffolding suddenly collapsed. As it plummeted into Golden Gate Strait, it took the safety net with it. Miraculously, two workers survived but 10 were killed, including Carl A. Anderson, a native of Sweden who had been living with friends on Flood Street in Sunnyside. Engineer Strauss ordered that a new safety net be installed within a matter of days to replace the damaged portion. By opening day, 7 months after its installation, the safety net had saved the lives of 14 Bridge workers.

After the Bridge’s grand opening, the safety net for Bridge workers remained in place. Yet, no safety net was installed or even considered for the public. At the time of this writing, nearly 87 years later, approximately 2,000 souls have jumped to their deaths (300 of these are unconfirmed) – that is an average of 37 people annually. By some miracle, over 30 people have survived the 240-foot fall despite hurtling downward at 75 miles per hour and, in 4 terrifying seconds, colliding with the frigid water and swirling eddies of Golden Gate Strait and as hard as concrete.

Decades of Hubris and Inertia

According to experts, the Golden Gate Bridge is the number one site for suicides in the world. So why is it that a public net was never installed despite proof of its effectiveness? Forty-five years ago in 1978, Dr. Richard Seiden of the University of California at Berkeley, published his epidemiological research about suicidal behaviors at the world-famous landmark. According to Seiden, of all the renowned landmarks across the globe (including the Empire State Building and the Eiffel Tower), the Golden Gate Bridge had remained unique:

“In every other instance the rash of suicides led to the construction of suicide barriers, which dramatically reduced or ended the incidence of suicides. Of all the suicide landmarks, the Golden Gate Bridge alone has failed to solve the problem with a protective hardware suicide deterrent … Although there is strong support from many segments of the Bay Area community, the Golden Gate Bridge Board of Directors has consistently dragged its feet on this issue ever since the barrier concept was first proposed over 30 years ago. Many reasons have been given for the delaying tactics but a major argument against constructing a barrier has been that it just wouldn’t work. Why wouldn’t it work? Because ‘common sense’ tells us that if a person is bent upon suicide, he will find a way and inexorably go someplace else to kill himself.”*

* To be clear, it took authorities at the Eiffel Tower 76 years (1965) to erect the first barrier after nearly 350 people had jumped to their deaths; authorities at the Empire State Building appear to have been more responsive, taking 16 years to install a barrier after 5 people leapt from its heights over a 3-week span in 1947.

And contrary to the unconscionable logic of Golden Gate Bridge authorities to not take preventive action, Seiden’s 1978 research found that of those who had been prevented from jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge, nearly 90% had not gone on to die of suicide.

Bridge authorities did periodically consider installation of a suicide deterrent, particularly after the spate of suicides Officer Symons witnessed in late 1953. In January 1954, they suggested raising the height of the side railings from 4 feet to 6.5 feet, confident that the extra 266 tons of steel needed, “would have no appreciable effect on the bridge.” At the very same meeting, the directors also reported that the installation of an additional safety net for Bridge workers assigned to a new lateral bracing project was on schedule.

After deciding a raised side railing would obstruct the view, in February the Board of Directors conceived an "anti-suicide" barrier constructed of several lines of barbed wire. A test site was erected on top of a 12-foot length of the side railing at a 26-degree angle. CHP Traffic Officer Jack Symons is seen in one newspaper report inspecting the concept. Bridge authorities surmised the barrier “might” prevent people from jumping and suggested a psychiatric review of the proposal. They were also considering “psychiatric help in preventing bridge suicides.”

CHP Officer Jack Symons inspects a concept for a suicide deterrent on the Golden Gate Bridge. From the Daily Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), February 12, 1954. Courtesy of Newspapers.com.

Unfortunately, Bridge directors felt no urgency for the matter. After not being able to reach an agreement, they extended their time for consideration of the proposals and after March 1954, no additional public comment was made about the barrier for the rest of the year and beyond.

Yet, Golden Gate Bridge authorities certainly had garnered enough revenue to not only continue their evaluation, but also consult with mental health specialists then design and install a barrier. Under a 40-cent toll in 1953-1954 (about $4.60 in 2023), the Bridge garnered revenue totaling $4,845 million, a value in excess of $56 million today.

And while they continued to hem and haw, an additional 25 despondent individuals would jump from the iconic structure in 1954, including a man and his son who leapt from the same point on the span 4 days apart.

At least one of these incidents would again involve Officer Symons. In March 1954, he noticed a woman who he believed was acting strangely as she loitered near the Golden Gate Bridge restaurant. Thinking proactively, he began monitoring her. Symons later noted, "I lost track of her for a while, but about 10 o'clock she came up to me and asked if it would be windier on the north side. She was acting a little strange, so I told her it was pretty cold out there and advised her to return to the city. Later, I learned she had asked a painter at the plaza how long it would take a person to die if he jumped off the bridge."

The woman, later identified as 59-year-old Ella C. Rhode of San Francisco, had instead gone inside the restaurant and lingered for two hours over coffee and doughnuts. Afterwards, she left the restaurant and joined two unsuspecting tourists for a walk on the Bridge. Symons added, "That's when I missed her." The tourists later reported that the woman had stopped 250 feet south of the south tower to look down and when they looked back a few minutes later, “she was gone."

The growing weight Officer Symons must have been feeling to be successful in preventing another death was finally lifted on April 3, 1955. With the assistance of three San Francisco residents and the man's wife, Cathleen, Officer Symons stopped a partially paralyzed Navy veteran, 30-year-old Michael Joseph Conroy, from jumping. During his military service, Michael had been injured when a heavy gun fell on him while arming a fighter plane. After undergoing several surgeries and later suffering a stroke, it appears Michael’s physical issues had become complicated by challenges with his mental health. So much so that a few weeks earlier, he and Cathleen had separated.

After the incident, Officer Symons escorted the Conroys and their two children to the Bridge district office where he learned of their recent domestic difficulties. Symons later reported that after speaking with Mr. Conroy for about 20 minutes and helping him calm down, he thought his behavior had become “perfectly normal.” The Conroys apologized for causing a disturbance and Symons allowed the family to leave.

Yet, Symons’ successful outcome would still end tragically. Just 2 days later in the middle of the night, Michael Conroy shot and killed his mother in her Clayton Street home as she slept. His father, a member of the San Francisco Fire Department assigned to fireboat Phoenix, quickly fled from the residence. Cathleen, waiting for Michael in their car parked out front, was likely unaware of what had just transpired. Early the next morning, her body was found in the grass near the Golden Gate Park Polo Fields, and Michael was found in their parked car nearby, dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

As if in agreement with Bridge authorities to just let people jump, the Daily Independent Journal of San Rafael claimed, "Two women would have been alive today if a Corte Madera man's suicide attempt off the Golden Gate Bridge had been successful Sunday." In defense of Officer Symons, his supervisor, CHP Captain Theodore Parnow, remarked that, "Unfortunately, none of us have a crystal ball and can’t foresee these things. Our officer judged the incident as a family quarrel.”

And because it was deemed a domestic dispute, Officer Symons was not required to draft an official report of the incident. To be fair, law enforcement did not yet have the tools or training for effective suicide prevention. In fact, it would be another 3 years before the first suicide prevention center would open in the United States, and another 40 before a national strategy for suicide prevention would be in place.

Unfortunately, since it was not CHP policy at that time to write official reports about personal or domestic matters, we do not know how many lives Officer Symons may have saved by preventing a person from jumping. Nor would those successes necessarily be reported in the news media. But the multiple tragedies Officer Symons had encountered while extending a helping hand may have taken its toll: by 1956, his beat had become the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge where far fewer suicides were reported. One must wonder if his transfer was by his personal request.

On his new beat, Symons’ public service would finally be rewarded with life beginning rather than ending. After stopping to investigate a car stopped at the San Francisco-bound Bay Bridge toll plaza, he found a pregnant woman ready to give birth. Her husband explained they had been on their way to Stanford Hospital in San Francisco (today, part of the Pacific Campus of California-Pacific Medical Center at Clay and Webster). Within moments, Officer Symons was present for what was reported to be the first childbirth on the Bay Bridge. The healthy baby and mom were then transported back to Kaiser Hospital in Oakland.

In 1958, the Symons family moved from Glen Park north to Santa Rosa where Officer Symons started his new patrol as a member of CHP’s Sonoma district. In June of that year as a representative for the CHP campaign to stamp out litter bugs, he distributed litter bags for vehicles.

Officer Jack Symons urges the public not to be a litter bug. From the Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), June 27, 1958. Courtesy of Newspapers.com.

Symons would serve with the CHP for 22 years before his retirement from law enforcement in 1975. His son, Jack A. Symons, Jr., would continue in his father’s footsteps, serving in both the Navy and the California Highway Patrol. Jack Symons, Sr. passed away in Santa Rosa in 1984 at the age of 67.

87 Years and 2,000 Lives Later, A Safety Net for the Public is Finally Installed

For the first time in Golden Gate Bridge history and 70 years since Officer Symons was on the bridge beat, the new Golden Gate Bridge Suicide Deterrent System (aka the Safety Net) is nearing completion. According to the Bridge Rail Foundation, since the Bridge’s grand opening in 1937 an average of 10 people each month were stopped from jumping by the compassionate officers of the California Highway Patrol (CHP), Golden Gate Bridge Patrol, and sometimes Bridge workers. And while 10 million people visit the world-famous structure each year, 85% of those who have died by bridge suicide lived less than an hour’s drive away (for more information about these demographics, visit the Bridge Rail Foundation).

According to the Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District and at a cost of $224 million, “The Net will be placed 20 feet below the sidewalk, extending 20 feet out from the Bridge. This design was chosen through a public process which solicited input from the community. The selected design allows open, scenic vistas to remain intact, while preventing anyone from easily jumping to the water below…it is modeled on similar systems, which have been installed in various locations around the world for almost two decades. They have been proven to be exceptionally effective deterrents to suicide.”

Views of the new Golden Gate Bridge Suicide Deterrent. Images from Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District, January 2024.

While there is relief that a safety net for the public has finally been installed, the apparent reason why it took 87 years is representative of the stigma society has placed on mental health disorders. In 2014, the New York Times reported that a record 46 people had plunged from the Bridge in 2013, while Bridge workers had stopped 118 others. It was at this time that Golden Gate Bridge authorities finally voted in favor of using toll money and federal and state funds to construct a barrier, in reversal of a long-standing policy.

Installation of a suicide barrier has been described by some experts as a "sign of care." In all fairness, Golden Gate Bridge authorities had been taking steps since the 1970s to enable “guardian intervention,” including increasing the number of foot patrols, closure of the pedestrian walkway at dusk, adding bicycle and motorcycle patrols in conjunction with the CHP, installing crisis telephones and closed-circuit cameras, and providing suicide prevention training to Bridge staff. While these interventions were successful in increasing the number of people who were prevented from jumping, they had no impact on the number of people who did jump. In fact, the number of bridge suicides continued to rise.

It was clear more needed to be done. One analysis pointed out there was “substantial evidence” for the effectiveness of suicide prevention barriers and that installing one on the Bridge would be a “highly cost-effective highway safety project” in terms of lives saved.

The New Suicide Deterrent has Already Been Validated

Given all the accumulated evidence, from the first historic safety net installed in 1936 for Golden Gate Bridge workers and including data from bridges and other precipices around the world, it may be no surprise that the stainless-steel deterrent now installed over Golden Gate Strait is already saving lives. During the net’s construction in 2023, the average number of suicides from the Bridge was cut by more than half. Those who did succeed had located gaps where the net was not yet installed, leading Bridge authorities to erect vertical fencing over those areas until all construction is complete. Once fully installed, the number of successful suicides should be reduced by an even greater amount. For decades, the answer had been in plain site.

We may never know how many people CHP Officer and Glen Park resident Jack Alvan Symons prevented from carrying out their final act. Whatever the number and for the remainder of their lives, many of them must have considered Symons their hero. And now that the new safety deterrent has been installed along his former Golden Gate Bridge beat, he would likely be proud and relieved to see that all the times he extended his hand and heart to help a soul in need were not entirely in vain.

As a high school senior, young Jack Symons had shared a premonition. In the end, the world really did come to him.

SITUS TERBAIK DAN TERPERCAYA

slot demo X1000

scatter hitam

slot toto

situs slot online

situs slot online

situs slot online

situs slot

situs slot

slot gacor

toto singapure

situs toto 4d

toto slot 4d

pg soft mahjong2

mahjong2

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

terminalbet

terminalbet

data pemilu

utb bandung

universitas lampung